Note from 2025: Before the microservices paradigm became dominant in the mid 2010’s, my paradigm of choice for highly scalable, loosely coupled distributed systems was the “worker” pattern described below. While I’ve encountered the worker pattern again just recently, it was in the context of a decade-plus old system due for modernization. As an older paradigm, I would not recommend using it as a first-choice for new systems today. However, as an illustration of separation of concerns, the worker pattern still makes a good example. I also think the analogies to movies and music here are fun.

Some of the principals that contribute to good, maintainable software architecture can sound a bit abstract. Their impact on your software during development and in deployment are anything but abstract, however! Adherence to good principals of software architecture helps you more rapidly produce a scalable, robust and maintainable system. Departing from them can leave you with a mess that never works really well, is hard to add new features to, and costs a fortune to maintain.

It is sometimes hard to articulate exactly what the adverse consequences of violating a given principal will be. These are “rules of thumb” which have been developed over generations of software architects—generally through analyzing what went wrong after a conspicuous failure had already occurred. Looking forward is always murkier. In the case of this particular principal, however, the consequences of ignoring it are fairly concrete: Your software will be significantly harder to build and enhance than if you do follow it.

The architectural principal we’d like to discuss is called “separation of concerns”. What this means in a nutshell is that one part of your system should not care about what the other parts are doing. Each piece of your system should care only about interacting with its immediate “neighbors” and “colleagues”, and not have to worry about the whole world simply to do its job. Architectures that successfully embody “separation of concerns” are sometimes described as “loosely coupled”, in analogy with mechanical systems. A coupling that’s “loose” is like a floppy mechanical spring joining two metal blocks. Moving one block has little if any effect on the other block, because the spring joining them is not very tightly coiled.

To illustrate this principal, let’s look at a couple of analogies from vocal music, and from theater.

As a young man, I used to sing choral music. In my favorite pieces, each independent vocal part stands on its own as, essentially, its own song. The part sung by the Soprano or the Alto is usually the “melody”—the song the audience hears—but I used to sing Baritone, which generally sings harmony, and there things get more problematic.

In a lot of Baritone and Bass parts, you end up singing just isolated notes that basically sound like a Tuba—just bah, bah, bah. In isolation, these notes make no melodic or musical sense at all; your part is certainly not a catchy tune you can hum. Such a part only makes sense when the other vocal parts are sung with it. This makes these parts more difficult to memorize and practice on their own and, in my opinion, often less fun to sing. Returning to our architecture discussion, I would say that such parts are “tightly coupled” to the other vocal parts, in the sense that they do not stand on their on, and instead depend on the other parts to give them meaning.

On the other hand, in some songs each vocal part has its own melody and “life”. One fun example is Neil Sedaka’s “Breaking Up Is Hard To Do” from the 1960’s (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tbad22CKlB4). The harmony part which goes “do do do do down, doobie do, down down, come on, come on, down, doobie do, down down”—while hardly Shakespeare—is contagiously fun to sing and catchy in its own right. It also works brilliantly as harmony to the other parts. (And, no, I’m not old enough to remember when this first come out! ;o))

A rather more sublime example is “Unto Us a Child is Born” from Handel’s Messiah (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MS3vpAWW2Zc) . Here each vocal part carries its own story and emotional content. In fact in this work of musical genius, Handel captures a Mother’s feeling vocally using the female voices, Soprano and Alto, while the Father’s emotions on having a new son are in the male Tenor and Bass lines. Individually each part is moving and powerful; combined they are truly brilliant.

Such parts that can “stand alone” I would describe as “loosely coupled” to the other parts. Each vocal part definitely adds value to the whole, and together they are far more powerful and brilliant. But each also stands alone—it has an independent life.

Another analogy is from the stage or the movies. In some dramas, some of the characters seem to exist solely to support the other parts; they have no independent existence. In fact, for these characters there may be little or no connection between one thing they do and the next, except as it relates to another player. These players also seem to belong solely to the play or movie—you can’t imagine them existing apart from it.

In a really compelling drama, on the other hand, you instantly believe that each character—even the “minor” ones—existed before the show began, and will continue to exist (assuming they weren’t killed off as part of the plot) as an independent being after the play is over. The drama itself just illustrates one episode in everyone’s lives, you imagine, rather than being the sole purpose for which these characters are called into existence. The drama may show the lives of multiple characters intersecting—either tragically, or for their good—but the strong sense is that each character is a person with their own life.

Maybe it’s just because I’ve seen it so many times, but it’s hard for me to watch this scene from the classic movie “Casablanca” without believing the main characters have a history that started long before the movie, including long-standing and complex relationships with each other (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7vThuwa5RZU). Each character, in other words, has a life of their own.

So what does this have to do with software architecture?

In a software architecture exhibiting “separation of concerns”, each software component also has a “life” of its own. That is, each component exists as an independent, well-defined entity. As in the analogy to vocal music and drama, each software component has its own “story” or “part” that exists independently of the other components.

Let’s take a look at what I see as a great example of the “separation of concerns” principal, which we’ll call the “workflow” pattern. This pattern is an elaborated and generalized version of the “Grep the Web” architecture described by Janesh Varia of Amazon in his paper “Cloud Architectures, June 2008. We have used variants and specialization of this pattern in several Cloud engagements, and have found it versatile and well suited to highly scalable systems:

Let’s first walk through the sequence of execution, and then talk about how this illustrates the “separation of concerns” paradigm.

- The client stores any required data or references to data in a shared input data repository

- The client requests that a particular type of activity be performed. The client’s activity requests are stored in a queue, and then processed sequentially by the workflow manager

- The workflow manager pulls the next activity off the request queue

- The workflow manager refers to the stored workflow definition(s) to determine the proper workflow to use for this particular type of requested activity

- The workflow manager creates a log record in the activity status data store that a particular activity has been requested at such and such a time

- Using the workflow definition for the requested type of activity, the workflow manager determines the first task that needs to be performed and determines which work queue contains workers that perform that type of task. The workflow manager then inserts a request into the appropriate work request queue. If requested in the workflow definition, the workflow manager may also use the timing service to set a timer which, when triggered, will signal the workflow manager that a task has not been completed on time.

- For each type of task, there is a pool of workers who perform that type of task. For example, there might be a pool of workers whose job is to input and transform data from one format to another. As it finishes its previous task, each worker examines the shared work queue for its pool, and tries to pull the next task off the queue. This is done in an atomic way so the worker either succeeds and the task is claimed, or it fails and the task is either left on the queue or is claimed by one and only one fellow worker. The first worker to claim the task owns it. In a cloud deployment, a worker would typically consist of one or more virtual machines.

- The worker performs its specialized task and stores any output data—or a reference to such data—in the shared output data repository. When it’s done, the worker places a “done status” message into the “task complete” queue that includes the task’s exit status (success, failure, etc.). Current task complete, the worker then returns to the shared work queue for its pool and competes against the other available workers to pull the next task.

- The workflow manager receives “done” messages from the “task complete” queue, and also messages from the timing service for tasks have not completed within the previously specified time.

- On receiving a “done” message from a given task, the workflow manager will cancel any timer alarm that may be scheduled against that task. It will then decide on the next task to be performed by using the exit status of the current task and consulting the appropriate workflow definition. For tasks that have timed out, the workflow manager also consults the workflow definition to determine the appropriate next task—which could be a cleanup and/or abort activity, for example.

- The workflow manager logs the exit or “timeout” status of the just completed task, and logs that the next task has been requested at a given time.

- The workflow manager then inserts a request into the appropriate work request queue for the next type of task, as determined above. If requested in the workflow definition, the workflow manager may also use the timing service to set a timer which, when triggered, will signal the workflow manager that a task has not been completed on time.

- Steps 7 through 12 repeat until all tasks as defined by the workflow are completed.

- After all the tasks in the workflow have been completed, the workflow manager puts an “activity complete” message in the activity complete notification queue together with the exit status information.

- The client pulls the activity complete message off the queue, and proceeds to its next activity as it sees fit.

- The client may download or otherwise access the output data produced by the execution of the workflow.

- Asynchronously from the workflow activity, the “Autoscale Manager” monitors the loading of all systems involved in implementing the workflow system. Consulting a set of external rules, which may say something like (for example): “Instantiate a new worker when the average utilization of the other workers in that pool is above 75%”, the autoscale manager creates or destroys cloud instances as needed to dynamically adjust to the current workload. It can also use predictive analytics to pro-actively scale the system in anticipation of future workloads (e.g. a shopping site needing more payment processing systems in the morning or the evening).

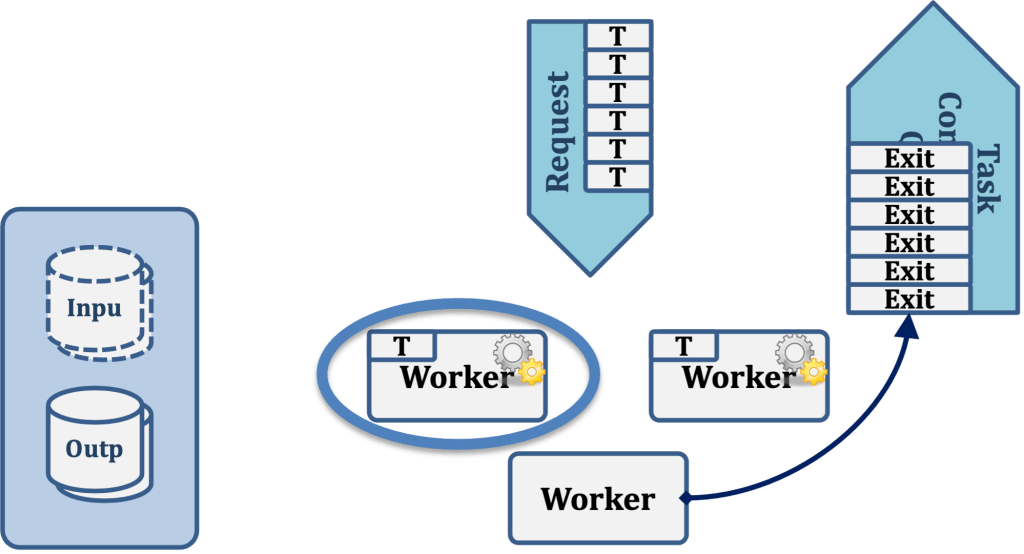

To see how this pattern illustrates the principal of “separation of concerns”, let’s zoom in and follow the activities of one particular worker, which we’ll call “Worker 1”, keeping in mind that the behavior of all workers servicing all request queues is identical. Let’s focus strictly on Worker 1 here; the other workers are independently performing their tasks in parallel with Worker 1, but have no interaction with it in any way. Each worker is autonomous and none knows about the existence of the other workers on this queue, or in any other queue.

In the first step of this example, Worker 1 tries to pull the next task off its request queue. Worker 3 is also trying to pull the same task in our example, but Worker 1 got there slightly sooner and thus claims the task, removing it from the queue. Worker 3 will note that it failed to pull a task off the queue and will try again to do so, but Worker 3 does not know or care about the existence of Worker 1. The two are entirely autonomous.

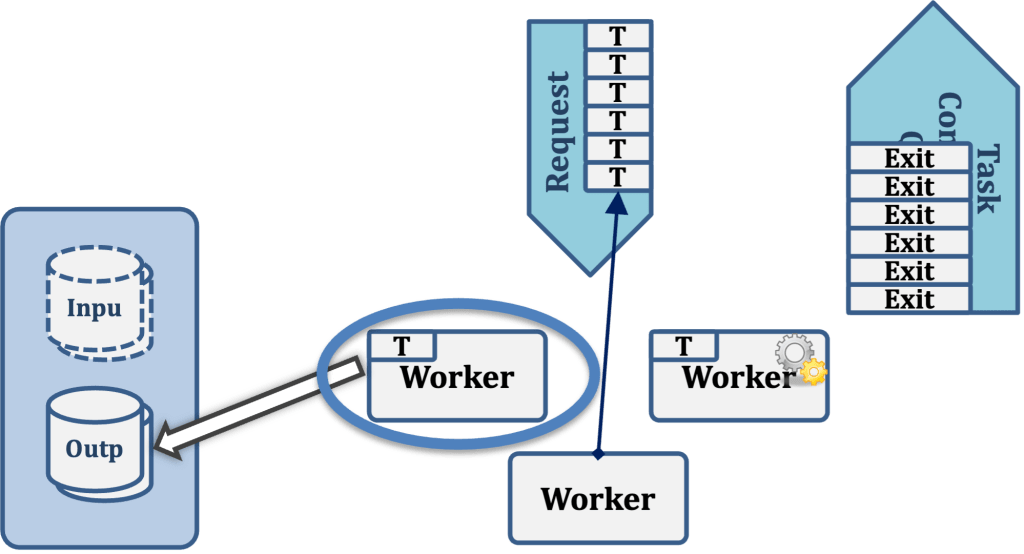

After successfully claiming a task, Worker 1 fetches any input data it requires to do its work from the Input Data store.

Worker 1 then performs its task, whatever that may be. For example, it may be to convert a file from one format to another, perform an analytic operation, or to do some other type of work.

Having completed its task, Worker 1 then writes any output data it has produced to the Output Data store.

Worker 1 now writes the exit status of the task just completed to the task completion queue.

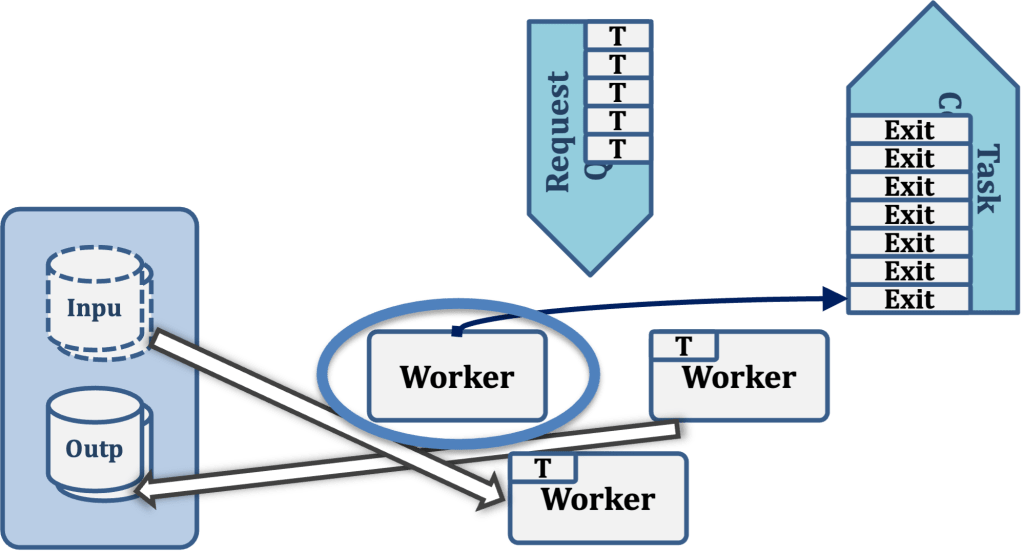

Worker 1 now tries to pull another task from the Request Queue, beginning the cycle all over again.

So, looking at the sequence of activities to be performed from the “point of view” of Worker 1, the “to do” list would look like the following:

- Get the next task from the request queue. If I fail to pull a task, or if the queue is empty, wait and retry later.

- Now that I have pulled a task, fetch the input data required to perform that task from the Input Data store.

- Do my work.

- Now that I’ve completed my work, store my output data to the Output Data Store.

- Push my exit status for this task onto the Task Completion Queue.

- Repeat the cycle from Step 1.

This is short, sweet and self-contained, much like the “down, doobie do, down down, come on, come on, down, doobie do, down down” portion of the song “Breaking Up Is Hard To Do” we listened to earlier. Note that the activities of this worker are completely self-contained; the worker is not “aware of” and does not need to be concerned about anything in the workflow architecture other than (1) the Request Queue; (2) the Input Data Store; (3) the Output Data Store; and (4) the Task Completion Queue. In particular, the worker is not aware of any other workers, and does not need to know how tasks get into the request queue, what is done (if anything) with the task completion status it writes; where the Input Data comes from or where the Output Data goes.

Another way of saying this is that terms of the workflow architecture, each individual worker has no “concerns”—that is, other parts of the system it must interact with—beyond the four listed above. The meaning of “Separation of Concerns” is exactly this: that each piece of the overall system may go about its own “concerns” or activities without being aware of or heavily influenced by the rest of the system. Each piece is autonomous, “living” a life of its own, much as two strangers living in the same apartment building. Those two strangers have some shared concerns—for example, perhaps the repair status of the elevators, the availability of parking spaces, or the handling of package deliveries to their building—but in any event their concerns do not directly involve one another and their direct interaction is either minimal or nonexistent. One of the strangers may move out of the apartment building without the other either noticing or caring.

That may sound like a lonely life for an individual, but it’s very good for a software component. The reason it’s good is that when one part of the system changes, few if any other parts of the system will “break” or be impacted in any way. For example, we could completely re-write the workflow manager or add features to it and it would have no effect at all on the implementation of any of the workers. This dramatically decreases maintenance costs, as well as allowing for rapid and safe evolution of the system—both as a whole, and of its various components. From an engineering management standpoint, product development is simplified since individual components can be developed or modified pretty much autonomously, allowing one to co-ordinate around availability of resources and other challenges.

Leave a comment