Scrum and the Copernican Revolution, Part I

Does the Agile / Scrum software development paradigm encourage innovation, or discourage it? My answer: it’s neutral, and can be used to do either. If both the customer and product teams show openness, imagination and indeed a little courage, Scrum can be a powerful force for achieving innovation. Scrum can also be used to more efficiently keep doing what you’re already doing—which is sometimes the desired result.

To illustrate these points let’s construct a little fantasy around a somewhat modified version of one of my favorite episodes in the history of science, the “Copernican Revolution”. Not using a software example will keep us in the process domain, rather than being distracted by the technology or particular business problem. Also, with my physics background, I just like this example! Even though it’s hopelessly anachronistic, we will imagine that astronomy in the 15th and 16thcenturies was done using the Scrum development methodology, and see how or if that would have changed history.

Nicolas Copernicus was an astronomer (among other things) who lived in Poland in the late 1400’s and early 1500’s. At that time in Europe, the widely accepted belief was that the Earth was at the center of the Universe and that the planets, stars, Moon and Sun rotated around the Earth.

Though this seems laughable to us today, it’s actually quite reasonable to suppose that the Earth is fixed in place. When you stand on the Earth and look toward the ground, the world seems quite stationary—and there is certainly no sensation of movement. It’s only when we look up at the sky that we need to broaden our view. The Sun and Moon rise and set. The stars circle around us in a predictable pattern of constellations, with different constellations becoming visible or being higher or lower in the sky at different times of the year. And the planets—well, the planets were the problem.

It turns out that the planets do not move in circles across the sky, as the other celestial bodies like the stars, Moon and Sun appear to do. Instead of always moving across the night sky in the same direction, the planets sometimes go backwards against the sea of stars, reverse direction, and start going forward again. Because of this initially unpredictable behavior, the English word “planet”, in fact, derives from the Greek word “wanderer”.

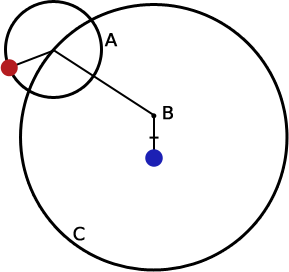

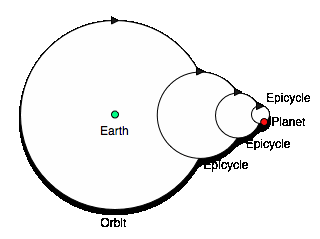

Let us suppose that the goal or “business requirement” of astronomy in the 16th century was to predict the motion of all the celestial bodies at any given time. Starting from the assumption that the Earth was fixed at the center of the Universe, this was a relatively straightforward task for the stars and our own Moon. To predict the back-and-forth motion of the planets, however, a complex system of what came to be called “epicycles”, or “circles on circles” was developed. In this system, the assumed circular motion of the planets around the Earth was elaborated by adding a circle-on-a-circle to the orbit. This model then described the sometimes backward motion of the planets.

These epicycles were sometimes further elaborated by adding epicycles to the epicycle itself, and so on, until a complex but observationally accurate model of the solar system developed over time.

Given that there were no general-purpose computing devices in the 16th century, special-purpose mechanical devices called “armillary spheres” were developed to aid in visualizing the future movements of the planets and other heavenly bodies. These spheres were complex and sometimes beautiful, and generally built for Royalty—often, we imagine, so that the King could brag of having the most beautiful and accurate sphere to his fellow sovereigns.

Now, in our fantasy, suppose that you are a 16th century software engineer assigned to work on, say, version 173.92.3 of an armillary sphere. The key business requirement of this project is to produce the most accurate model of planetary movement yet developed, using fresh observations to construct more and more elaborate epicycles—and to do this before any other Monarch has such a sphere.

Since our project is using Scrum, the backlog is full of epochs derived from the business requirements, like “As a Monarch, I want my armillary sphere to accurately reflect the new observational data for Jupiter before any other Monarch has such a sphere—or else”, where the “or else” was personally added by the King during his project review. There are similar Epochs for Mars, Saturn and so on. There is a Scrum team assigned to each planet, with a “Scrum of Scrums” coordinating the overall project. You are a scrum master, and your team owns the “Mars” epicycle Epoch.

During the release kickoff, the product owner reminds you that there is a lot of pressure to meet the deadline for this project, and that there is a demo planned for the King’s upcoming visit, which is just six sprints away—three of which you need to reserve for the sphere mechanical construction team and other tail-end tasks. You and your team work with the product owner to do release level planning, elaborating the backlog and making your initial story point estimates using planning poker. You make an initial assignment of stories to sprints. The schedule is tight, but it looks like you can make it.

Sprint one passes without major incident, with you and your team working on tasks related to the top priority story, which is “As a software engineer, I need to compute the additional epicycles required to account for the 2 degree inconsistency measured in the position of Mars during the last eclipse”. A couple of days before you finish up the sprint, a junior member of your team, named Nick Copernicus, comes to you with an interesting idea.

Nick sees you in the cafeteria at lunch one day and says “I’ve been thinking about this whole epicycle thing…”

“Yes, Nick?” you say.

“Yes,” he replies, “I wonder if we haven’t ended up with a needlessly elaborate architecture here because we started from a false assumption.”

“I’m listening, Nick, but I’m not sure what you’re saying” you reply.

“Well”, says Nick, “we’re starting out with the assumption that the Earth is stationary and the Sun and planets go around it, right?”

“Of course,” you reply. “We’ve been doing it that way since the 3rd century B.C.”

“Yes. Now I’ve been doing some thinking, and if we were to assume that the Earth goes around the Sun, it turns out that this whole Epicycle thing just goes away.”

“Goes away?” you respond, startled. “What do you mean, goes away?”

“Well, if we assume the planets all make circular orbits around the Sun at different distances, then for people on Earth the planets would naturally look like they’re going backwards sometimes. Let me draw you a diagram…”[i]

He does, and a long discussion ensues. It’s a heated debate, but by the end of it you are convinced that he’s right, and that you and your team are patching a faulty architecture which is about 1700 years overdue for refactoring. You and Nick decide to go talk to the Product Owner right away.

The Product Owner is a good guy, but much more business-oriented than technical. He listens patiently, and surprisingly does not offer any real opposition to Nick’s radical idea. However he says “Guys, look, this is an interesting idea. As you know, though, we’re on a tight schedule. If we don’t have this armillary sphere ready to demo in 5 more sprints, heads will roll.”

Knowing the King is coming to see the demo, you are not sure if the “heads will roll” statement is literal or metaphorical—and somehow you feel reluctant to ask for clarification.

This is the “innovation” decision point in Scrum / Agile: How much risk do you take to incorporate radical innovation into your product, and when do you take it? The glib “textbook” answer is that if you’re really following Agile, you will have strong and complete test automation and so should never fear to radically refactor your architecture right up to the last minute. Real projects, however, often have incomplete test coverage, and the real or perceived limitations around schedule and business goals can cause architectural improvements to be deferred—sometimes indefinitely. Is this the right thing to do?

More in part II.

Credits

Photo of planetary motion from http://antwrp.gsfc.nasa.gov/apod/image/0312/retrogrademars03_tezel.jpg

Images from wikimedia.org

[i] To see how both models explain the retrograde motion of the planets, see the animation at http://www.sciences.univ-nantes.fr/physique/perso/cortial/bibliohtml/epiclc_ja.html and http://alpha.lasalle.edu/~smithsc/Astronomy/retrograd.html.

Leave a reply to Scrum and the Copernican Revolution – Digitally Indigenous Cancel reply