This month, August 2012, is my 30-year anniversary as a software engineering professional, receiving my first official paycheck in August 1982. By both inclination and profession, my tendency is to look ahead, not back. As I think about this milestone, though, I can’t help but remember what it was like “way back when.”

I thought it might be fun to share my personal experience of how the software industry has evolved over the past three decades, including some of the gadgets and technologies I have loved—and sometimes lost—along the way. I invite you to come with me on this journey, looking backward for a change, instead of thinking about what’s next!

In the Beginning

I started working with electronic computers when I was about 14 years old. Today, that would not be unusual, but back then “personal computers” did not yet exist. However, through a strong interest in science and technology—and some fortunate circumstances—I was able to begin working with mainframes at a fairly early age.

I was spared having to program using punch cards; I was just young enough to avoid the “batch processing” era entirely. My first programming experiences were with “timesharing systems.” Though we still needed to drive to the building where the enormous computer was physically located, once we got there each user had an individual terminal (screen and keyboard—no mice yet!) that provided what we would now call interactive on-line access.

My first high-level programming language was APL. This is a truly bizarre array-oriented language that uses specialized symbols, rather than words, as commands. The language was extremely dense and efficient; you could invert a matrix with a single character and write a complex program in one line of code (which at the time I loved to do). For example, this program identifies all prime numbers between 1 and R:

As you can see, APL makes Perl syntax look verbose and obvious. Why anyone thought it was a good idea to teach this particular language to high school students (ages 13 to 17-years-old) is beyond me. Nonetheless, I loved it and spent many happy nights and weekends figuring out clever things to do on my next visit to the computer. I especially enjoyed hacking through the timesharing system to take over my friend’s terminals and insert timebombs and other little presents. Ah, youth!

I kept using computers and various languages throughout my high school, college and grad school careers. However, I never even considered studying computer science. (I was a physics major with a strong interest in mathematics.) At that time, computer science was a discipline in its infancy. The people who studied it planned to work for IBM, a large bank or the government—none of which I aspired to do. My interest at that time was in computers as tools, not as ends themselves. I also had an interest in electronics, both as a hobby and as a study, and learned about logic circuitry and computer internals—which turned out to be pretty handy for programming, as well.

My First Computer

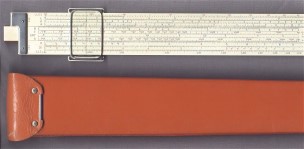

Until the mid 1970s, I had not owned a computing device other than mechanical computers. The first “computer” I ever owned was a slide rule, which I inherited from my grandfather and learned to use when I was about 12. This is a mechanical device consisting of wooden parts that uses logarithms to multiply, divide, compute powers of numbers, and perform trigonometric computations. It did not add or subtract (you were expected to be able to do that mentally). A slide rule is an instance of an “analog” computer, as opposed to a “digital” computer; the numerical values along the slide and other parts make a continuous number line, not discrete values. A knowledgeable person using a slide rule could generally achieve a precision of two and sometimes three significant digits.

For college I saved up to buy what I considered the best slide rule available for physics, the Keuffel & Esser Log Log Duplex Decitrig. I had to visit the MIT bookstore to get one since they were considered quite advanced and only sold at engineering-oriented schools. Slide rules were still widely used by my fellow physics majors when I started college, though I was among the first to switch to an electronic pocket calculator when they became affordable. I cringe to think of it now, but I did indeed sometimes wear my slide rule on my belt in its foot-long orange case. Thankfully I never got any trouble for this because the other kids thought it was cool (or I was so “uncool” that I just thought they did…).

The first digital computer I ever owned was a mechanical device called a “digicomp.” It was built from a kit and made out of plastic, believe it or not, and could be programmed to perform three-bit binary addition and logical operations (AND, OR) through the placement of a series of hollow plastic pegs. This was not a practical device—it was a toy—but it was indeed a real (albeit very primitive) programmable digital computer.

Electronic computers simply did not exist for home use before 1976. Even the idea of owning your own computer in the early 1970s was like aspiring to buy a jet airplane today. Similar to today’s jet airplanes, computers in the early 1970s were expensive (millions or tens of millions of dollars), and they required special facilities and staff for maintenance. Owning your own electronic computer was firmly in the realm of science fiction when I was in high school.

Programming for Calculators

A watershed moment in my relationship with computers was the introduction of programmable scientific pocket calculators by Hewlett Packard in the mid 1970s. Hewlett Packard had produced a series of desktop programmable calculators in the 1970s that I had used in school. However, these were physically large (covering most of a desk) and quite expensive. The ones I used were owned by the school. HP also introduced the first “pocket calculator” in the early 1970s (the HP-35), but it was not programmable and was quite expensive—about $3,000 in today’s currency.

In the mid 1970s, however, HP introduced the very first programmable electronic device I ever owned: the HP-25C pocket calculator. It was priced at $200 (about $1,000 in today’s currency). My father paid the lion’s share, and I excitedly made up the difference with earnings from a part-time job. This calculator was truly programmable, with conditionals and loops (using GOTO statements), though programs were limited to a maximum of 49 steps. The programming language was quite low level, analogous to modern-day assembly language, though with the addition of pre-programmed mathematical functions such as the trigonometric functions “sin” and “cos.”

As a grad student, I later acquired an even more sophisticated calculator, the HP41C. Personal computers had been introduced by the late 70s (the first Apple computer shipped in 1976), but the Apple computer was quite primitive in terms of its scientific capabilities, which is what I was interested in at the time. Though they were rapidly added, floating point operations were not even supported in the initial languages available for the Apple computer. IBM PCs, DOS and Windows did not yet exist. If you were interested in mathematics, the HP41C calculator was the apex of the programmable calculator world, offering extensibility through plug-in modules and a magnetic card reader for extra storage.

Because my family situation required me to relocate away from the university while I was finishing up my research, the bulk of the mathematical calculations for my Ph.D. thesis were performed on an HP41C calculator that I programmed. I suspect that the program I wrote (testing certain quantum chromodynamic assumptions by calculating a range of hadron masses) may be one of the largest ever written on that device. Certainly if I’d had access to a university computer, I would have written in a higher-level language than the near-Assembler available on this device.

Still, because of the size and complexity of my program, I learned a lot about structuring code for readability and maintainability. In particular, I learned that it’s possible even on a pocket calculator!

Here’s an example of an HP41C program to compute the factorial of an input integer:

Imagine writing thousands of lines of code like this, and then debugging and maintaining it! On the plus side, you could call functions to do numerical integration and other rather sophisticated mathematical operations. Well, you learn to work with the tools you have available, and I completed the numerical processing needed for my thesis using my HP41C.

Looking Forward

My next blog post, which can be found here, explores my first decade in the computer industry, from 1982 through 1992. If you have questions about my experiences or would like to share your own stories, please feel free to leave a comment below.

Leave a comment