This blog is Part II of a multi-part series that explores my thirty years in software engineering and how the industry and technologies have evolved over three decades. To read Part I of the series (focusing on the years prior to 1982), click here.

A Full-Time Software Engineer

In late 1982 I got a very happy and life-changing surprise: we learned that my wife was expecting our first child! My daughter Anna’s impending arrival motivated me to shift from being a full-time graduate student in physics to a full-time software engineering professional, finishing my Ph.D. thesis write-up in my spare time.

Not incidentally, my new job came with a computer, the “Durango F-85.” I was looking forward to using the computer (during off hours and with client approval, of course) as a word processor to type up my thesis.

The F-85 was an 8-bit Intel 8085 computer with an integrated printer, “green-screen” display device, and “high density” (480Kb) dual 5.25 inch floppy drives. The version I used ran an operating system called CP/M. The pre-Windows Microsoft operating system MS-DOS (which ran on similar Intel hardware) first shipped in 1982 and conceptually borrowed much from CP/M.

The Durango was a loaner from my client and their choice of hardware, not my own. A full-featured Durango F-85, including a 40Mb hard drive, retailed for $13k in 1982 dollars—roughly the equivalent of a mid-range luxury car (about $40k today). As my business grew, I would eventually have several of these machines. In fact, one currently sits in a box in my storage unit, much to my wife’s chagrin. I know I should get rid of it, but thinking about how much money these computers cost, I could not stand to part with them all.

Lessons in Market Dominance: Part I

The early 1980s were extremely fluid times for what we then called the “PC” (personal computer) industry, and it was extremely unclear what standards would emerge and who would be the winners. I’ve seen this pattern recur many times since then around different technologies — Cloud/BigData being an analogous area today. However, when IBM entered the PC market in 1981, it was obvious that they—together with the newly introduced operating system MS-DOS—would be the market-maker and define the standards.

As my first MS-DOS machine, however, I did not pick the IBM PC but instead chose a cheaper one with better graphics called a “Victor 9000.” I’ve learned a lot from that decision, which turned out to be the wrong one for both myself and my client—who on my recommendation bought lots of them, circulating them to their offices worldwide. Though the Victor machine was arguably “better” from a technical and price standpoint, it was completely trounced in the marketplace by IBM.

The lesson I learned, which I carry with me to this day, 30 years later is: the best product does not always win. Many factors affect market success, and technical superiority is not always—or even usually—the most important factor (a hard lesson to accept for a technical guy).

An Early Adopter

Another recurring situation that started for me in the 1980s has been the attention I sometimes get on airplanes when I bring the latest cutting-edge device on-board with me. Since I travel frequently and am also an early adopter of new technology, the new devices I carry with me often attract curiosity and appreciative looks from my fellow business travelers. I’m not intentionally trying to show off, but I have to admit I enjoy it when a cabin attendant drops by and asks breathlessly, “Is that a new XYZ?!”

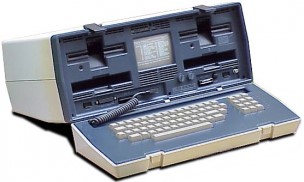

The first time I remember this happening to me was in the early 1980s, when I traveled with one of the first “portable computers” ever invented, the Osborne 1. The Osborne was portable in the sense that it could be hand-carried, but it was not what we would today call a laptop or notebook. The machine weighed 24 pounds (11 kilos), the weight of an average toddler (18 month-old child). Today’s “portable” machines are five to ten times lighter: a typical laptop might weigh about 5 pounds (2.3 kilos), with a lightweight machine like a MacBook Air weighing less than three pounds (1.4 kilos).

When I first carried my Osborne 1 onto an airplane for a business trip, the heads turned and the necks swiveled the way they would today for someone carrying the very latest just-released smartphone. I remember my fellow business travelers shooting admiring glances at my new “portable computer” as I walked down the aisle of the plane, carrying it in one hand. I hadn’t expected this reaction, but it was fun.

Adventures in Word Processing

The Osborne 1 also ended up playing an important role in helping me complete my Ph.D. thesis. The word processing features of the Durango were indeed great for text processing—much superior to the manual typewriter I would have used just a few years earlier. However, the Durango’s high-quality embedded and proprietary printer did not have software that could produce the mathematical symbols I needed for my thesis.

The Osborne 1 was more “open” and came bundled with a word processing package called WordStar. In one of the (hardcopy) computer magazines I regularly read, I saw an advertisement for an add-on package that allowed WordStar to print mathematical symbols. I sent away for this—by snail-mail and with a paper check enclosed—and it arrived by mail some time later on floppy disk.

Since I already had a popular Epson dot-matrix printer, my thesis production problem was almost solved now—except for the logistics. All the formulae for my thesis were hand-written. Getting them all into the computer was a huge undertaking. Fortunately, my then very pregnant wife came to the rescue and typed the literally hundreds of equations for me on my Osborne 1, while I was transcribing the text into the Durango’s word processor. We then literally cut-and-paste, with glue and scissors, all the equations into the proper place in the separately typed text. As the final step, I Xeroxed the pasted-up pages onto the mandated thesis paper supplied by my University, and the result came out looking pretty good.

When I wrote some additional scientific papers later in the 1980s, the state-of-the-art had evolved considerably. I was able to use the “LaTeX” markup language, which allowed you to embed equations into the text itself, thereby avoiding the need for cut-and-paste. LaTeX was available as a stand-alone postprocessor for text files, rendering postscript pages that you could then print. LaTeX and the typesetting language “TeX” from which it inherits were in many ways parallels to SGML and later, of course, HTML. Their separation of content from layout and rendering was especially intriguing to me, and it has proved itself to be a very useful paradigm in many contexts.

Lessons in Market Dominance: Part II

After completing and defending my thesis and receiving my degree, I got on-board the market trend and became a confirmed IBM PC user, using Microsoft operating systems and languages. The shakeout in the computer industry was fairly quick, and I had learned an important lesson: market dominance tops technical superiority almost every time.

The only hope a new technology has to prevail, in my experience, is to create or define a new market segment where it can achieve market dominance. Otherwise, someone whohasachieved dominance with a previous or a worse technology will gobble the new one up—hopefully for a large sum of money, but sometimes not. If none of these things happen and the new technology never achieves market dominance, it will languish and/or die. A grim picture, perhaps, for those of us who focus on creating these new technologies!

My advice to overcome the cycle is to find the best marketing and business people you can and make them your allies. And if it’s open source, find a way to publicize it! But in any event, technology success is much more about achieving recognition and dominance in the market than it is about the technology. It is a bitter truth, but the best technology does not always win, not even in the long run.

I do see this situation improving with the more overtly Darwinian model of open source, where technically better packages sometimes do win out. Even so, given at least an acceptable level of technology, judging the winners is much more often a matter of how much market share and popularity they can gather quickly, rather than pure technical superiority.

Introducing Email

It wasn’t until the late 1980s that email started being widely used as a communication mechanism. Can you even imagine having no email or other electronic communications available to you other than voice telephone calls? Even fax machines did not become popular until the late 1980s.

At a startup where I worked in the late 1980s/early 1990s, as an off-hours project I set up the company’s first email system using uucp. To do this, I manually strung cable between the serial ports (RS-232; USB ports did not exist yet) of selected machines and the multiple serial ports on a Unix machine that I designated as our inhouse mail server. The in-house mail server made a timed dial-up serial connection to a central mail server to send and receive external messages.

It’s hard to imagine today, but like most companies at the time, we did not have Ethernet. Other than for electricity and land-line telephones, there was no cabling in the building except for an occasional point-topoint serial connection between physically adjacent machines. Ethernet had been invented, but it was not in widespread commercial use until the 1990s. Ethernet hubs were invented along with Ethernet itself in the 1970s, but the first commercial Ethernet switch did not ship until 1990, and routers were generally implemented in software on a multi-port computer. And, of course, there was no world-wide web to connect to yet!

I believe that creating the cross-over cables for these connections was the last time I used a soldering iron at work. Starting in the early 1990ʹs, email and internal networks became commonplace in the high-tech community, and I have used them ever since.

The Evolution of Programming Languages

The first programming language I used commercially was, I’m embarrassed to say, a rather primitive form of Compiled BASIC (“Bascom”). I used this language not because it was a good one, but because in 1982 it was the ONLY affordably priced compiled language available for the CP/M operating system. A compiled language was essential for commercial software because otherwise you’d be distributing the source code— there was no way to obfuscate it. Incidentally, Bill Gates personally helped write the code for the BASCOM compiler in the late 1970s.

My first compiler arrived from Microsoft on an 8” floppy disk. It shipped in a three-ring loose-leaf binder with mimeographed (a pre-Xerox copying technology) instructions. This format was obsolete technology even in 1982, and I had to have a service migrate the binaries to the more modern 5-1/4” floppy drives I had on my Durango.

The 1980s were an innovative time for language development, and I had heard of a language called “C. Unfortunately, the only available commercial-quality C compiler for the CP/M operating system on Intel (called Whitesmith’s C) cost $600 per CPU (about $1,800 in 2012 dollars), plus a per-client distribution license of, I believe, about $30 per seat. This was definitely prohibitive, especially the client-side cost.

With its lack of structure, BASIC was not suitable for the type of larger-scale applications we were beginning to build, so I had a talk with one of my close friends from college who had worked as a developer on the US east coast at several national laboratories. He advised me to migrate to C, which I did as soon as the more affordable Manx Aztec C compiler came out (around 1983). I subsequently migrated to the Microsoft C compiler after 1985, when it became available. I learned C by reading the Kernighan & Richie book and all the related “white cover” C and Unix books, and I never looked back.

The fact that I am self-taught in computer languages may be shocking to the current generation of developers who consider a Masters in computer science to be a minimum entry-level credential. But keep in mind that in 1982, the people who had computer science degrees were primarily mainframe developers working in large corporate IT departments or for the government developing accounting and back-office applications with Cobol; or else they were researchers at computer companies and academic institutions working on operating systems and compiler development. No credential or even training existed for developing on the personal computer. The people who developed PC software in those days were much like me: interested in technology, but with a math, science or other type of engineering background. In fact, Bill Gates and Steve Jobs did not even finish college—they had no academic credentials whatsoever! Nonetheless, they did pretty well.

My choice of the C language proved a good one. Essentially every production (as opposed to scripting) language I have used since (C++, Objective-C, Java) has derived from C—so this was clearly the right choice versus, say, Pascal. This choice also taught me something else that has stuck with me: When you’re making a big technology decision, talk it over with the smartest people you know. Even Steve Jobs himself followed this principal. When I later worked at NeXT, it was routine for Steve to drop by engineers’ and managers’ offices and say “I’m thinking of doing XYZ—what do you think?” He wouldn’t always (or even usually) take your advice, but we felt listened to, and he got a variety of perspectives on his decision. Occasionally, he may even have learned something that changed his mind. Smart.

Late in the 1980s, I had the opportunity as a consultant to help Borland develop the compiler validation suite for a then brand-new language for microcomputers called C++. When it shipped in 1990, Borland’s Turbo C++ became the first version of C++ for MS-DOS to achieve widespread developer popularity, and it helped pave the way for that language’s emergence in the developer community. It came with an integrated IDE and had available a closely coupled debugger, setting a pattern for many languages to come.

By this time I had become a strong advocate of what was called “structured programming” and a “software tools” componentization approach for development using procedural languages. Once I encountered the new object oriented paradigm, I immediately understood the value of the encapsulation and potential re-use that C++ provided. It clearly solved what until then had been a real problem. Little did I realize, though, that this language would set the tone for the entire next decade, with Object Oriented programming having a huge impact both on the industry and on me personally.

Looking Forward

Next week, I will talk about the decade from 1992 – 2002. This was a pivotal time in software evolution, where in many ways the current software engineering era was created. To read my previous blog about technology in the years prior to 1982, click here.

Leave a comment