From a computing perspective, the 1990s were recognizably more “modern” than the 1980s. Much of the technology we as software engineers use every day today—Ethernet, C++, the Java programming language, the Windows operating system, email and the internet, graphically rich interactive development environments (IDEs), hand-held smart devices—all entered widespread use in the 1990s.

In this next installment of my blog series, I will touch on the evolution of mobile phones and personal digital assistants; email and the world-wide web; operating systems; and languages, processes and object orientation during this decade. You can find my previous blogs on technology from the 1980s and earlier at their respective links.

Mobile Phones & Personal Digital Assistants

Mobile phones actually did exist prior to the 1990s, but they were so expensive to purchase and to use that few people had one. In 1989, a Motorola MicroTac phone cost $2,495 (about $5,000 today), and the monthly service charge was about $500/month ($1,000 today). CEOs, stock traders and the very wealthy used these devices, but not the common person—or even engineers. It was very unusual in the USA to have a mobile phone until the late 90s.

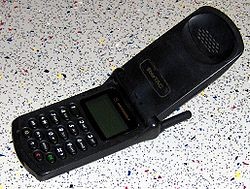

It wasn’t until around 1997 that I acquired my first mobile phone, a Motorola StarTac with carrier Cingular (now AT&T). This is only fifteen years ago, which seems pretty recent to be obtaining such a fundamental technology—but again, I was actually a pretty early adopter. Few of my colleagues at Apple had a cell phone at this time, and this one was seen as pretty cool. As I recall, my StarTac was a TDMA phone and cost about $250 ($350 or so today)—not so very different from a topquality phone today.

There was no fixed price rate plan, either; everything was charged per minute of use. The minutes were fairly costly, maybe $0.10 or $0.20 per minute of “talk time.” Still, being a parent with young teenage children at the time, it was well worth it to be constantly reachable by them when I was at work, or vice versa. I saw this device as a huge benefit, even though its only “feature” was voice conversations. SMS soon became available with later generations of digital devices, though with my original phone it was not an option.

I am not sure if world-wide roaming was available at any price. If it was, it must have been enormously expensive—it’s not cheap even today. When travelling overseas, the common practice at that time was to rent a physical phone specifically for the country you were going to visit. I remember doing just that on a trip to the Czech Republic as late as 2002. Nowadays, most countries —including the US— generally (though not exclusively) use GSM, which enables you to localize your device with a simple switch of the SIM card.

When thinking of today’s “smartphones,” it’s surprising to note that the “smart” part actually preceded the “phone” part historically, not the other way around. What we would today call “smart” devices were, in the early 1990s, called “personal digital assistants” or “PDAs.”

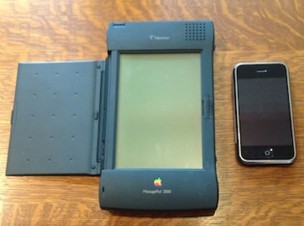

Among the first of the PDAs was Apple’s “Newton MessagePad.” The Newton was a recognizably modern device that, though larger and noticeably heavier than today’s smartphones, was easily hand-carried. It performed many of the same functions that we today take for granted on our smartphones, such as calendars, contacts, email, calculator and so on.

However, it lacked any integrated communications capability, except for an infrared port that only communicated Newton-toNewton. In practice, it synched with a computer via a cable.

The initial version of the Newton shipped in 1993, the same year I joined NeXT software. The first version I purchased, however, was the “MessagePad 120,” which became available in 1995. I was inseparable from my Newton, and I carried it with me to meetings and (to a lesser extent) at home, like I carry my iPad today.

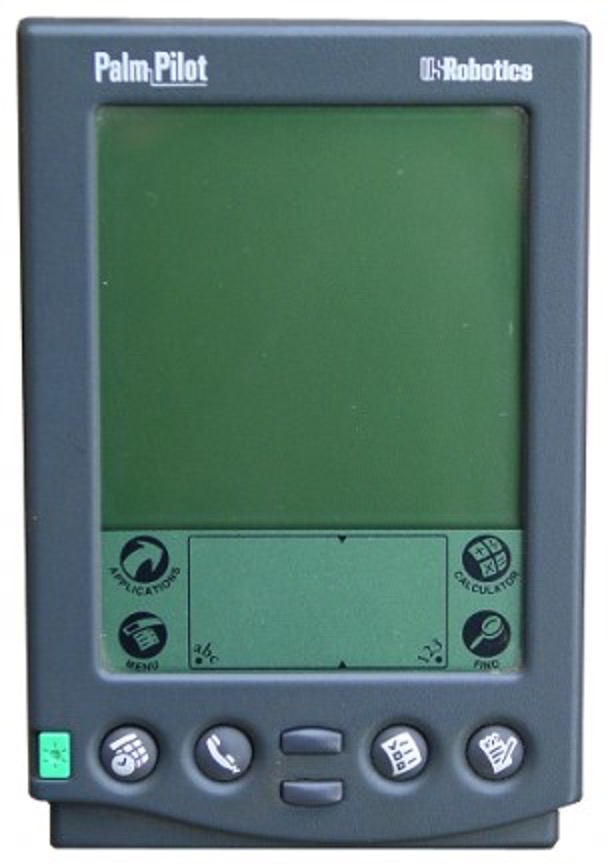

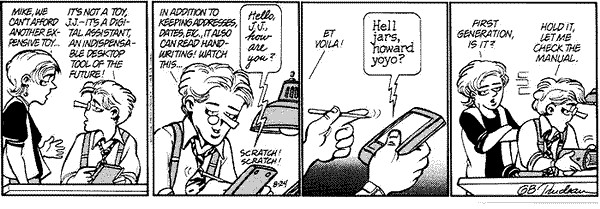

In 1996, Palm Computing shipped a competing PDA called the “Palm Pilot.” Neither the Newton nor the Palm system had a keyboard; data entry was done through a touchscreen interface using a stylus (a pen with a rounded tip and no ink). However, the difference between the two systems was that Apple’s Newton recognized your natural handwriting in a full-page format, wheres the Palm required you to enter a single character at a time in a small rectangular data entry area, using a stylized type of writing. For example, the letter “T” was entered as a sort of inverted, mirror-image “L.”

While the Apple system may have had a theoretically more appealing approach, it was obvious from the time the Palm shipped that there was a key difference between the two systems: the Palm’s mechanism was reliable and worked, whereas the Newton’s mechanism was unreliable and frequently did not work. The Newton’s handwriting recognition was so erratic that it literally became a joke. You needed to double-check every word you entered to make sure it was not translated into total nonsense. The Palm’s character recognition mechanism—though it had a learning curve (you needed to practice for a couple of hours)—was surprisingly easy to master and was thereafter quick and accurate.

This is an instance of another recurring situation in software that has many names: “The perfect is the enemy of the good” or, as Steve Jobs used to say it, “Real artists ship.” Often 80% of the product value can be delivered simply and quickly, with the remaining 20% taking nearly all the effort. Generally—though not always—the right decision is to complete the simple part that delivers 80% of the value immediately and get the product in front of end users. You then listen to what the customers say and respond to their feedback. The part you thought was important—and that takes nearly all the effort—may turn out to be totally unnecessary. That’s the essence of Agile and the foundation of most currently successful companies.

My speculation is that someone at Apple insisted that free-form handwriting recognition was the most important feature of the product and that customers could not live without it. Therefore a huge amount of the implementation effort went into that very difficult problem. In the meantime, someone with a simpler solution that was “good enough” for customers—and, more to the point, actually worked—came and took away the PDA market.

It’s a real art to decide what’s important and must be right, and what will be less important to customers. On this decision, whole enterprises rise and fall. Generally the best way to find out is to try something and ask—that’s the Agile way. In my opinion, Steve Job’s best talent was knowing what a customer would accept and what they would not. He was not necessarily reliable in this, but when he was right, he was spectacularly right. For the rest of us, I firmly believe that the Agile approach of “try, get input and adjust” is the right one.

I remember having my Newton with me at a company meeting at NeXT Software, where I was sitting in the front row to make a presentation. Suddenly Steve Jobs, the NeXT CEO, sat down next to me. He gestured to my Newton and asked, “Can I see that?” I handed it to him, and — somewhat to my surprise — he pretty much took it apart. He flexed the cover’s hinges, removed it and put it back on; checked the battery compartment; looked at every mechanical button and weighed the device in his hands. I said to him, a little awkwardly, “You know, some day these handheld devices are going to change the world.” He gave me a little half-smile, and as he handed my Newton back to me said, “Not that one.”

I remained loyal to the Newton for a few more years, until Apple canceled production. I then switched to the market leader, adopting a series of Palm Pilots as my PDA.

Email & the World-Wide Web

In addition to laying the foundations of the smartphone revolution that would come in the next decade, the 1990s saw the launch of the world-wide web. When I joined NeXT software in 1993, email was somewhat novel—though I’d already been using it at work for several years—and the world-wide web did not yet exist.

The lack of the web made it challenging to do some of the things we take for granted today—for example, supplying customers with updated release notes and technical information in between releases. NeXT actually shipped its software to customers on CD-ROMs and bundled the release notes and support tips (called “NeXTAnswers”) with each version. If any new information was discovered in between releases, it was provided to customers over the telephone case-by-case—a slow and expensive process.

Shortly after I joined NeXT, I was in a staff meeting where the topic was improving customer support. I spoke up and said, “At my last company, we had an automated FAX-back system where customers could use an IVR (interactive voice response) system to have the latest support notes FAXed to them in between releases. It worked pretty well.” Steve, who was running the meeting, turned to me and said, “Great idea. Make it happen.”

Support was not my functional area, and I was already quite busy recruiting and organizing my team. Still, when the CEO tells you to make something happen, that’s what you do—especially if it’s Steve Jobs! I remembered a very bright young IT guy / developer who had been in the new employee orientation meeting with me a few weeks before, and I went to go see him. I explained what I wanted to do with NeXTAnswers, and he said, “Sure, we can do that. But why not make it an automated email response system, as well?”

Remember, in 1993 email was brand new as a widespread technology. AOL had only started offering email to the public two years earlier. Many technology businesses had it, and I’d used it for several years. But it was clearly the coming thing. So I said, “Great idea. Let’s do it!” We pulled together a small team, got the necessary servers and equipment, and got the system up and running. In addition to being a big success with our clients, we were able to charge extra for a premium service, and we set up the team as a separate department within NeXT.

About a year later, the same guy came back to me and said, “You know, the world-wide web is getting to be a big thing. Would you help me pitch creating a website to host NeXTAnswers? A website would be much better than either FAX or email.” At that point (1994), I’m not sure I’d ever seen a website. Still, I said, “Great idea. Let’s do it!” I helped him make the pitch, and we got the support for creating what later developed into the NeXT corporate website. At the time of its launch, http://www.next.com was one of relatively few commercial websites on the world-wide web.

The web evolved extremely quickly, and websites rapidly evolved from static pages to dynamic sites, with e-commerce being a leading driver. Around 1995, NeXT developed a technology called “WebObjects” that originally took advantage of Objective C’s remote proxy mechanism. This was initially developed as a test automation tool, but the inventors rapidly realized its value as what we would today call an application server. WebObjects was used to power a number of early ecommerce sites, including (in 1997) the online Apple Store. Even today, the WebObjects application server is used for iTunes and other Apple offerings.

It’s astonishing to think back on how rapidly technology evolved during the 90s. From 1991 to 1996, we went from email being a relative novelty to deploying recognizably modern shopping sites on the world-wide web.

Operating Systems

In terms of operating systems, the 1980s were a CP/M and MS-DOS decade for me, whereas in the 1990s I did a lot of my work on Unix. I began using Unix at a startup in the late 1990s, where I actually ported part of the BSD “curses” cursorcontrol library to System V. At Rational, I had a Sun SPARC workstation that ran SunOS 4 (later relabeled as Solaris 1) with a Motif/X-Windows GUI. And of course NeXT ran on a BSD implementation on top of the Mach microkernel (as does its descendent, Apple’s OS X).

Ironically enough, my first work on Microsoft Windows happened while I was at Apple in 1997. I was leading the development of a “Web catalog” application based on the Java API version of WebObjects. This system supported the remote authoring of web catalogs using a web browser to upload images; it also performed merchandising and other e-commerce related tasks. Obviously we needed to support the Windows browser systems since they dominated the market, so I was one of relatively few people at Apple with a Windows desktop machine on my desk. This was, of course, dual-boot so that I could also run “NeXTSTEP for Intel!”

While at Apple, I also had a Mac PowerBook Duo that, I think, was my first laptop ever. Laptops had been around for several years already, but since none supported the NeXTSTEP operating system, I never bothered to get one while at NeXT. Apple did, however, have some beautiful hardware running MacOS. I chose a slightly older model that was “subcompact” and had a docking station for when you were working at your desk. That machine was definitely one of my all-time favorites, and I still have it in my garage (my wife, as you’ve probably guessed by now, is long-suffering).

Languages, Processes and Object Orientation

When I joined Rational (now part of IBM) in 1991, it was an island of object-oriented, iterative software development in a sea of procedural languages and waterfall development. Rational was a boutique firm specializing in the Ada development language and associated development tools. The company’s primary focus before 1991 had been architecture, consulting, process, and tools development for government customers. I joined the new “Commercial” business unit that would focus on the more commercially-oriented C++ language and on products for business customers.

I did have home computers at this point—several Apple Macintosh’s that my children and I used. These were networked over AppleTalk via twisted-pair telephone wire. The connecting wires were initially strung from the ceiling, giving the appearance of a kind of literal “home-wide web”—something my wife was not at all pleased about. These machines were for fun (and the kids’ homework), not really for work. My work from home was done on an “X-terminal,” a physical machine that connected over a dedicated ISDN line to my Sun / Solaris / Motif desktop at the office. Photo courtesy of Jim Walsh (all rights reserved).

Grady Booch, later co-inventor of UML, was one of the two architects on our team. Grady was already famous in the software community as the developer of “Booch Notation” for the architecture and design of object-oriented systems. He was also the author of the “round-trip iterative gestalt” methodology for software development. The development of our initial product, Rational Rose 1.0, was to be a showcase for both Booch Notation (which the tool supported) and Grady’s methodology.

When it first shipped in 1992, Rational Rose was, at 250,000 lines of code, one of the largest “pure” C++ programs that had been developed up to that point. We used early iterations of Rose to design later iterations as an embodiment of Grady’s “round trip” methodology—and a foreshadowing of the Agile practice of continuous integration and deployment that would be introduced about a decade later. The process we used to develop Rational Rose served as an important input to the Rational Booch Method development process, which was a precursor to the later Rational Unified Process, or “RUP.”

RUP and its Booch Method predecessor were more concurrent, iterative software development models that began to displace the waterfall methodology in the 1990s. While they still had distinct project phases as in the waterfall approach, these methodologies also advocated timeboxed iterations and concurrent development and testing throughout the project. In fact, Iseult White, author of the original Booch Method books, interviewed me and other Rose project participants to help document this new approach to software development.

Similarly, we used a weekly build and deploy cycle at NeXT that today we would call “Sprints.” We incorporated the new check-ins and built the entire 5.5 million lines of the NeXTSTEP operating system weekly, and then deployed the latest build onto every engineer’s desk. If someone broke the email system, we found out very quickly! Not every weekly build went out companywide, but toward the end of the release they did, and the entire company ran on the pre-released version. As you can imagine, Steve was not shy in his feedback, so we had an additional (and very strong) quality filter before the first customer saw it.

In the early 1990s, Steve Jobs liked to describe NeXTSTEP as an “Object Oriented Operating System.” While I’m not sure an operating system fits the strict technical definition for object orientation, this description did have merit. Each component in the operating system—for example, the “print” dialog—had a declared and well-defined set of inputs and outputs, and encapsulated behavior. Steve was proud of pointing out that while virtually every program in Microsoft Windows had its own implementation of the “print” dialog (and still does today), every program in NeXTSTEP—regardless of authorship— shared the common OS-provided dialog.

Like any “object oriented” system, a program could override or augment the default behavior it inherited; but unless the programmer did something extreme, the dialog the user saw was recognizably the same for every application. This degree of reuse and commonality made the system easy for end users to learn, and it made programming far more productive because you did not need to re-invent the wheel.

Probably the culmination of the object-oriented revolution of the 1990s was the widespread adoption of the Java language (around 1996). It was pretty clear to everyone—even to us at NeXT—that Java, not Objective C, was the wave of the future. At NeXT, we began migrating to Java and away from Objective C even prior to becoming part of Apple, and this trend continued thereafter. It is one of the ironies of the computer software field that Objective C has again come into prominence by being the programming language of the iPhone.

It is indeed true, by the way, that Java borrowed many concepts from Objective C. I once had the opportunity to meet James Gosling, original inventor of the Java language, and he confirmed to me that Objective C was in fact an influence. While we’re on the topic, Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the first web browser, also credits NeXTSTEP’s ease of programming as the reason he was able to create the first web browser. I don’t have this statement personally from him, but I do believe it.

Finally, to close off this language section, I must confess that my on-again / off-again love affair with Perl began in the late 1990s. Whenever I do system control or text processing, my go-to language is Perl. I’ve been told that I’m old fashioned and should be using Python, but I must admit that I do keep coming back to Perl when I have a quick task to get done.

In Conclusion

Looking back, I’m struck by how the seeds of Agile, the smartphone and object-orientation all grew out of the 1990s—and from the early 1990s, at that. Next week we’ll take a look at the 2000s to current day, exploring how they led to both a high Velocity and truly “flattened” world.

NOTE FROM 2025: This series, written for my then-30th Anniversary as a professional software developer in 2012, consists of the following parts: “pre-history” (before I began working professionally in 1982), 1982-1992, this blog (1992-2002), 2002-2012, and my predictions for the next 30 years, from 2012 through 2042.

Leave a reply to Topical Index – Under Construction – Digitally Indigenous Content Cancel reply