Early in the decade of the 2000’s, I was at a startup developing a predictive analytics solution. Our objective was to host the advanced “decision analytics” engine we developed as a SOAP-based web service using a business model that was then called “ASP” (not to be confused with the Microsoft technology of the same name). ASP, standing for “application service provider”, is what we would today SaaS (“Software as a Service”) or even by the rather unfortunate acronym AaaS (“Analytics as a Service”).

At the beginning of the decade words like “Agile”, “VoIP”, “WiFi”, “Open Source” and “Smart Phone” were just beginning to enter the engineering mainstream, while words like “Cloud Computing” had yet to be spoken—at least outside advanced R&D labs. Still, at this 2001 startup we used technologies that even today would be regarded as mainstream: Java, Struts, SOAP, Tomcat, SVG, and an XML decision model representation to name a few. Our server OS’s were Windows and (if memory serves correctly) Linux. Our development methodology was the then brand new Agile methodology, “Extreme Programming”. Even our telephone system was recognizably “modern”: the then-new Cisco VoIP Call Manager.

If I were to make the same technical choices today that we made back in the early 2000’s, I doubt if any but the more technically aggressive people would be very concerned. All the technologies we selected back in 2001/2002 are still very much with us and in widespread use ten years later. However I would not get the kind of throughput, scale, flexibility and rapidity of development that the current technology choices make available to me. In choosing the older “proven” technologies, I would be making in some sense a “safer” choice, but at the same time I would not be leveraging the best technology that’s available to me today.

To implement a similar “Analytics as a Service” product concept in a similar business situation today, I’d make totally different choices. My guiding principal would be to build a product ready for the next decade, and to take maximum advantage of current technical advances to give me the “biggest bang for the buck”—the most benefit for the least engineering effort. Prominent among these technologies would be Cloud and bigdata technologies. These would give me massive scalability and reliability basically “for free” in terms of programming effort.

My first step—as it was then—would be to gather together the smartest people I know and brainstorm our options. Today, these options would no doubt include an elastically scalable Cloud deployment model; a NoSQL distributed data store such as, for example, Amazon DynamoDB or Cassandra; RESTful interfaces; JSON; perhaps the “R” programming language (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R_language) for some aspects of decision modeling; and maybe Python Pyramid or node.js for the interfaces and d3.js for the graphs. There are lots of good options, and I learned long ago that the best technology decisions are made by listening to the smartest people you know in the space.

This real-life example is a good illustration of how I’ve experienced technology evolution in general over the last thirty years. In 2012, Java, Open Source, XML, SOAP, VoIP and the other technologies we selected a decade ago seem like good, solid, well-validated choices. However when we made these selections back in 2001, they were seen as “cutting edge” and risky. In fact some people in that startup were acutely uncomfortable with these choices at the time. And they had some valid reasons. Operationally, you could not go out and easily hire people in 2001 that already knew SOAP, for example—this was brand new technology. Even Java was still fairly cutting edge in the early 2000’s compared to, for example, the C++ language that I’d worked with a decade before at Borland and Rational. And because it was newer, Java programmers tended to be harder to recruit and more expensive—another argument that was used against the “new” language.

It’s a similar situation today with the more “modern” Cloud-centric technologies I mentioned above. While each of the technologies I would consider today is well proven by highly successful companies in large-scale deployments, the mainstream is still uncomfortable with many of these choices. Even where the “modern” choices solve a real need, whether or not a given team designing a new product can and should embrace the latest technologies will end up depending heavily on the non-technical factors of the project. In some situations, the skills and inclinations of the current development team may limit the options that can be realistically employed. Schedules, politics and other non-technical considerations may also limit a team’s ability to try a new approach, however much they would like to.

In cases, though, where the advantages are compelling and create real value for the product, my advice is that you should embrace the newly proven paradigms wherever possible—even if it’s a little scary and the team needs to stretch. This is not to say that it’s a good idea to embrace every new idea that comes along—that’s more a question of “fashion” than of substance. But where a new idea emerges that offers real value, and where other serious and thoughtful people are using it to successfully solve real-life problems, then it’s worth your while to learn about it and take advantage of it. I can predict with some confidence that a product making appropriate use of the new best-of-breed Cloud technologies has a much better chance of still being “current” when I write my 40th anniversary blog in 2022 than one written using technology that was cutting edge in 2002.

We certainly did see language and tools evolution in the last decade: Java grew “fatter” with J2EE / JEE and then got “thinner” again as the Spring / POJO paradigm grew dominant. Ruby on Rails emerged as a popular and highly productive choice for web applications. Python—though with us since long before the 2000’s—rose to prominence as a first-class product development language. And perhaps most surprisingly to those of us who have been around a while, javascript—once considered by engineering snobs as a second-class language for HTML hackers—has emerged as a first-class language both on the client side and the server side. Though not novel conceptually, the emergence of distributed NoSQL databases to store unstructured data (text, for example) and non-relationally structured data (such as graphs, trees and key-value pairs), together with the tools to take advantage of them, is also of incredible importance. And the SOA / ESB (Service Oriented Architecture / Enterprise Services Bus) / Service Orchestration paradigm rose to prominence in various industries and is still widely used in the Enterprise Software space (though no longer very frequently in the ISV space).

While in no way minimizing them, from my own personal perspective in product development I would classify the changes on the language and tools front in the decade of the 2000’s as more evolutionary than revolutionary in nature, compared to past decades. There are other recent changes, however, that have been very much revolutions. In terms of disruptive changes that have occurred in the software industry over the last decade, my short list would include:

- Outsourcing

- The move to browser-based systems and ubiquitous mobile service, leading to a “flattened” planet

- Hosting and the elastic scalability paradigms of the Cloud (Big Data, compute elasticity) and the democratization of massively parallel compute paradigms like Map/Reduce to take advantage of it

- The Agile software development paradigm and the widespread availability of powerful, ubiquitous and free (or nearly free) software and people who know how to use it

- Smart devices, tablets and “physical world” aware devices (location-based services, etc.)

- Self-authoring and publishing of content on the world-wide web (facebook, twitter, blogging, “web 2.0”)

Outsourcing

By the beginning of the 2000’s, I had already worked on several distributed development projects—a memorable one being the Japanese Kanji version of NeXT’s Software’s NeXTSTEP Operating System (3.1j). I’d also worked with outsourced providers of specialized services such as software CD-ROM duplication and distribution. Still I had never done actual software product development outsourcing, and indeed was very skeptical of the whole concept. From my point of view at the time, software development was challenging enough when everyone was in the same building. Putting the barrier of timezones and oceans between teams seemed like a recipe for failure in the late 1990’s.

I had encountered outsourcing as a concept in software development back in the 1990’s in two contexts. One was the use of specialized firms that focused on a particular and usually highly technical task—for example, Intel / Windows video device driver development. These companies tended to be US based (or later in the decade Eastern-Europe based) and small—maybe 20 people or so. The other type of outsourcing was generally done for IT departments of large companies. They used staff in low-cost geographies—with India being the most popular—to augment in-house programming staff for some relatively low-end (technically speaking) special-purpose work—for example, for “Y2K” conversion.

(For those of you not familiar with “Y2K”, there was an issue around date arithmetic with the turn of the century from 1999 to the year 2000, the year otherwise known as “Y2K”. Many programs that represented the year as a two-digit string or integer such as “95” assumed that the numerical value of the last two digits of a later year (for example, “99”) was always greater than the numerical value of an earlier year (for example, “93”). This assumption was no longer true across the century boundary since year “00” occurred after year “99”, not before. Uncorrected, this assumption would cause accounting and other date-dependent systems to fail spectacularly on New Year’s Day, 2000. Writing at a short distance of just over 12 years after this event, it’s hard for me now to imagine that the world could ever had developed so much software with this fatally flawed and short-sited assumption—but we sure did!)

The Y2K problem led to the explosive growth of the India IT outsourcing industry because once the tools were in place, the inherently date-critical nature of the problem offered only one solution to compress implementation timelines: add staff. While plowing through millions and millions of lines of mostly COBOL code was an enormous undertaking, the fix to each individual instance of non-compliant code, once found, was generally straightforward. This allowed large numbers of relatively low-skilled programmers to be effective at finding and fixing Y2K problems. As a side effect, the India outsourcing industry was launched.

Where there are large numbers of relatively low-skilled programmers, some fraction of these people will prove to be very smart and, over time, become high-skilled. Other high-skilled, smart and generally more senior people are needed all along to supervise and guide the lower-skilled ones, and educational systems were put in place to produce and grow more talent. While outsourcing remained mostly an IT-centric phenomena in the early 2000’s, the capability also rapidly developed to the point where some Indian outsourcing companies were able to field Silicon Valley caliber resources—first in the testing, support and maintenance areas, and later in product development.

This era is where my own involvement with outsourcing began. By 2002, I had left the “AaaS” startup I described above and was working at an enterprise software company that had already made the decision, before I joined, to try outsourcing. My team was selected for the trial. I did not mind this at all since it would grow my team—in fact, nearly double it in time. I was on the vendor selection committee—quite interesting in itself—and we picked a vendor based in Hyderabad, India. I recall asking one of my Indian colleagues at the time which major Indian city Hyderabad was closest to; I had never heard of it before. My colleague looked at me rather strangely, saying: “Hyderabad is a major city—it’s the forth largest city in India and has about six million people.” So I got a map and looked it up: Hyderabad is in the south of India, about 550 km north of Bangalore by road.

I don’t think my general lack of knowledge about India was unusual in the US at the time—I think it was fairly typical. Certainly we in the software industry had worked side-by-side with Indian immigrants to the US for many years—but we talked about software, not so much about India the country. For me, one of the first experiences I remember with an Indian colleague was in the early 1990’s. One of my fellow managers was an older (than me at the time) Indian gentleman who had been in the US for about 5 years when I met him. I remember one day he took me aside and said “Jim, may I make a personal statement?” I was rather puzzled, but told him to go ahead. He said “You know, I think you are the most “American” person I have ever encountered.” I didn’t know how to react to this statement, but chose to take it as a compliment and thanked him. My Indian colleague continued: “You know, just a few years ago, I would have had no idea how to deal with someone like you; I would have run screaming from the room. I take it as a real success and it shows me how much I’ve grown that we can work together so well.” After this I really didn’t know what to say, so I mumbled something vaguely positive and quickly changed the subject.

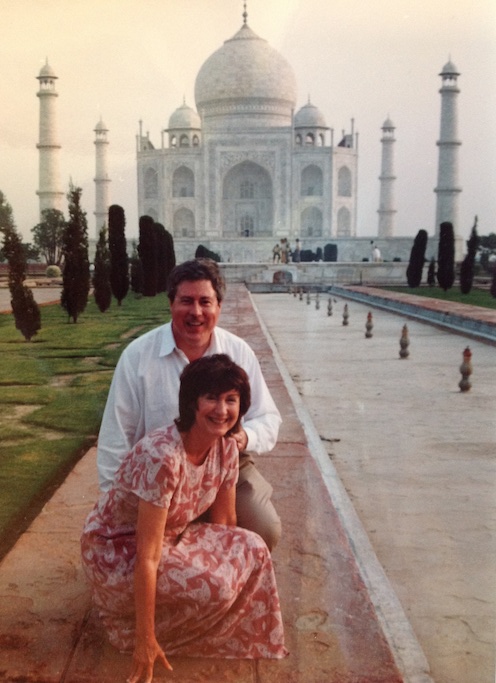

My ignorance of India in the early 2000’s was such that given the surprisingly low cost per head (relative to Silicon Valley at the time) I had real and (as it turned out) totally unfounded concerns about whether or not the people on my outsourced India team were exploited workers. This bothered me so much that I got on a plane and went over to Hyderabad to check. As it turns out, I need not have worried. I found happy, well-treated people whose physical working conditions were actually better—literally—than those I had experienced at the San Francisco-based AaaS startup I had recently left. I found out that the wages that were paid to them permitted them to live comfortably middle-class lifestyles by the local standards—far better, in many cases, than their parents. Their jobs were considered prestigious and offered a great deal of upward mobility.

As for the caliber of the people, with one or two exceptions (which I fixed), I found myself thinking that if they were in the US, I would hire these people.

Fortunately I was not in a situation where I was ramping up in India in order to lay off in Silicon Valley—this time. But in Hyderabad I found myself thinking: Would it be the right thing to do to deny these great, hard-working people employment for the sole reason that they live in India and not the US? To me, at that moment, that seemed like the most “un-American” thing I could possibly do.

A few years later, I joined another Enterprise Software company specifically to help them establish an offshore development center in India. Looking back on it I actually did not have a lot of practical experience with outsourcing at the time I joined. However with my one success I still had far more experience than anyone around me—and more than most in the industry at that time. This time our center was to be in Bangalore—which I had heard of. Over time, it grew to about 180 people and ended up “owning” the development, end-to-end, of two core product lines with only a limited on-shore presence in both areas. We also later opened a second development center in Eastern Europe that was highly successful in developing portions of our highly technical analytics product line.

Today it is almost unthinkable for a software product company to NOT have an offshore development component. Even startups often begin with an outsourced team, either immediately or shortly after creating their first prototype and getting funding to develop a product. This reliance on outsourcing is because the demand for speed of development has grown higher while spending on engineering is capped by the expense ratios of the best-performing companies—who generally all use outsourcing.

Another key driver of outsourcing is the relative lack of availability of skilled local resources. In 2012 I learned of a job posting in the Silicon Valley area that offered a salary of $160k per annum for an iPhone iOS developer with 2 years experience. While you need to wonder how long such a job would actually last (Days? Weeks?), at the same time no sane company would make such a posting if the skillsets they needed were readily available. Shortage of talented, skilled engineering labor is a huge limiting factor for technology companies in the US—and an important driver for outsourcing. If experience has taught me one thing, it’s that there are smart people everywhere, throughout the world. As long as that’s true, and as long as economic growth is not uniform globally, there will clearly be a need for outsourcing.

One side effect of outsourcing is that in the 2000’s I became a frequent global traveler. I had always done some degree of business travel, some of it international, but nothing like what I experienced in that decade. Our youngest child turned 18 in 2003 and soon after left for University. While we missed her enormously of course, not having children at home enabled me to travel extensively, sometimes bringing or meeting my wife along the way. In the early 2000’s I traveled first as a relatively early customer of outsourced product development services; later in the decade I was traveling because I had switched to the provider side. There were several years during the decade when I spent more time traveling overseas than I did at home.

I actually don’t know how many international trips I took and how many miles I travelled in that decade, but it was a rare year in the 2000’s when I didn’t fly the equivalent of multiple times around the globe. My frequent flyer balances on more than one carrier range up into the high hundreds of thousands—and those are just the miles I haven’t yet used.

Technology flattens the world

One of the most striking facets of traveling around the world in the 2000’s was how easy it was, in historical terms. There’s nothing technology can do about timezones, which are built into the shape and size of the earth. There’s also no way of changing the fact that even traveling near the speed of sound, it’s a long way from my home near San Francisco International Airport to Bangalore, Delhi, or Eastern Europe. But short of that, international travel in the 2000’s imposed relatively few inconveniences beyond the long plane rides and the fact that, when I got there, my colleagues and family tended to be asleep while I was awake, and vice versa.

By 2012 many of the technologies that made convenient travel feasible became so commonplace as to seem mundane, but they very much changed the face of business travel over the last decade, mine included.

On the everyday living side, browser-based banking and bill paying services meant that I did not have to come home anymore just to pay bills—which, prior to the early 2000’s I would have had to do for a few bills at least. This, together with direct deposit of my paycheck into my bank account, enabled me to be away from home for literally months at a time, which I sometimes was. The global interconnection of Cash Machines (known in the US and some other places as Automated Teller Machines or ATM’s) meant that my normal debit card from my bank “at home” could be easily used to get local currency from any cash machine in the world. My Visa, MasterCard and American Express cards were accepted world-wide, meaning I did not need traveler’s checks to pay for food or other living expenses while traveling. While we aren’t conscious of it very often, all of these are enabled by software and telecommunications technologies.

Similarly, all my work could be done over the internet. I actually don’t need to “be” in any specific place to do work—I can work as effectively and with the same access to tools and information in a café in Vienna Austria as I can in my office in San Jose California. Even my office landline automatically forwards calls to the mobile phone in my pocket. Other than to be in physical proximity to the colleagues who at any given moment happen to be in GlobalLogic’s San Jose office, there is absolutely no reason I can’t be halfway around the world and do the same work.

This has not been true for very long, by the way. If you’ve been following this series you may recall that as advanced as Rational, NeXT Software and Apple were, in the 1990’s I had to be physically or logically plugged into the corporate network to access certain tools and files. I needed a dedicated ISDN connection to “work from home” on my X-terminal at Rational, and a VPN connection over dial-up or ISDN modem to remotely mount my home directory when working from home at NeXT (theoretically possible but painfully slow—it was easier to work offline and email files back and forth). Today, every corporate tool I use is either browser-based or installed on my laptop, tablet and in some cases on my smartphone as well. Even my work email and file storage is browser-based (Google Apps). I don’t need to use VPN or any other network connection technology, enabling me to work exactly the same way—with the same access to tools and information—from the garden of my Silicon Valley home or a hotel in Bangalore as I do in from my office in San Jose. In fact I don’t even need to use the same machine or type of device—the bulk of my files are either stored on-line or automatically replicated between my devices.

Of course the bigger picture is that what is true for me as a business traveler is the same thing that has enabled product development outsourcing to be effective: With current technologies, it literally does not matter where you do your work. We will always need to account for the impact of timezones on real-time communications and the human imperatives behind face-to-face communication and relationships, I believe. But my original concerns about outsourcing back in the 1990’s are addressed by today’s technology: Even if we’re in the same building or campus, unless you and I are literally face-to-face, we’re now using exactly the same technologies and communication mechanisms as we would use if we were on opposite sides of the planet. In the latter case, the corridor between our offices is just really, really long. That’s how I’ve come to think of it.

Another technology that was essential for my international business travel is the email-enabled mobile phone. The fact that my business associates or family members could always dial the same number and my mobile device would ring wherever I was in the world, without my caller having to know where I am geographically, makes today’s flexible styles of travel possible. My associates and I may be in the same building today and on different continents tomorrow. Yet we can consistently receive our messages and make our calls as we travel, without having to explicitly alert any centralized system to re-route these communications. We take this for granted today, but the amount of infrastructure, standardization and legal / financial agreements that were required in the industry to accomplish this seemingly simple task is mind-boggling.

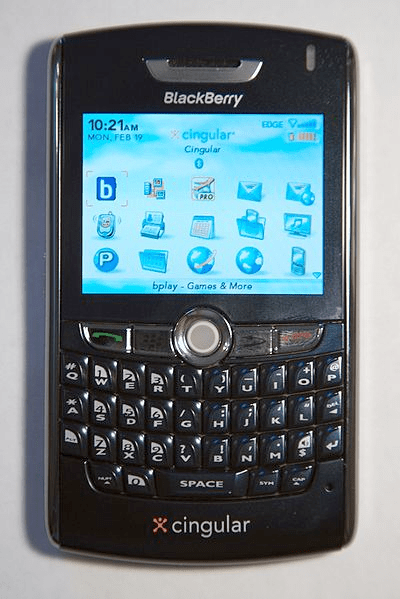

Not to say that mobile devices are perfect for travel, even today. For a number of years in the 2000’s I was a Blackberry user. Even when more advanced phones became available, the Blackberry had a compelling advantage: international data roaming was cheap and unlimited—a flat rate of $50/month, as I recall. For someone who was mobile as much as I was—and pre-iPad, mind you—being “always connected” anywhere in the world and being able to read and respond to my email on a pocket-sized device was a compelling advantage.

Voice roaming rates were not standardized, however, and in fact they were quite expensive. I recall that on my first visit to India with my new Blackberry, the data roaming was indeed cheap, but the voice roaming charges came to nearly $2,000 USD over a three-week trip! On my next trip, I acquired an Indian mobile phone with an India-based carrier for use when I travelled there, and thereafter avoided the roaming charged entirely. I still used my Blackberry for email, though!

Hosting and the Cloud

My previous decade’s extensive business travel was made possible—or at least much more effective—by the technologies that provide location-independent services for banking, cash, communications and on-line applications. Outsourcing, too, was also made effective by location-independent delivery of services and information over the internet.

This same location-independence trend—when applied to compute resources—gave us first hosted services and then (quite different) the Cloud.

The wish to co-locate compute resources with high bandwidth internet connectivity gave rise first to the “co-location” center, and then the concept of hosted services. People gradually realized that they did not have to have computing resources literally within the walls of a building they owned in order to control those resources. With virtualization providing the means to do it, a further step was taken when people realized they did not even need to own the physical hardware their applications were running on. The ownership of “virtual” machines that ran on top of the hardware gave nearly as much control, and with infinitely greater flexibility, than owning the machines themselves. Out of this realization, the cloud was born.

Invented in 2006[1], the cloud made possible a new style of programming and a new scale of applications that can address the needs of the whole planet. That sounds like hyperbole, but with roughly a billion users—about half a billion of which use it daily—facebook alone touches roughly one seventh of the world’s population. And that’s just one site. About one third of the world’s population has internet access. When we talking about developing applications at “internet scale”, the cloud and it’s accompanying “big data” technology is a necessity.

Equally remarkable to the development of cloud technologies themselves is the fact that so many of these technologies have been made available for free as “open source” products. Giant companies like vmware, HP, IBM and many others are practically falling over each other to give us powerful, free software to create and enhance our own cloud infrastructures. Other giants such as Twitter, Yahoo! and Google are inventing and giving us powerful “big data” (10 TB up to many petabytes and beyond) analytics services such as Hadoop and Storm to process extremely large data sets, unstructured information, and streaming data.

While not entirely altruistic—improvements are for mutual benefit, including (and sometimes especially) that of the giver—there is no question that these gifts of software to the development community are far-sighted and extremely beneficial. Their benefit is not just to developers but to everyone who buys or uses software. The availability of free technology of this power and scope is completely unprecedented in my experience and, I believe, in the history of computer science. The effects of free cloud and big data analytics software will be extremely far-reaching, beyond what we can currently foresee.

One thing I am pretty sure of: We are currently in a “golden age” of software development. I’m not predicting that things will get worse—in fact, I think they will continue to improve—but there is no question that as developers and as users we have never had it so good in terms of choices and price. What is possible and practical now is so immense it’s hard to convey. But the convergence of mobile technology, big data, cloud and new software development and interpersonal communication paradigms are propelling us forward to a very exciting future.

Self-authoring and Publishing

The fact that you’re reading this “blog” shows that you are well aware the world has changed profoundly over the last ten years through the ubiquity of self-published media. At the beginning of the decade, technical people were able to author and post web pages with personalized content with relative ease and at relatively low cost. What we couldn’t have done, though, is read the musings of approximately 31 million fellow bloggers—that is the number of people blogging (that is creating content like this) in the United States alone. Blog readership is even larger—over 300 million individuals read the blogs hosted on just one popular site (wordpress)[2]; there are many other sites which host blogs as well.

We are all encountering similar explosions in self-published content in videos, social networks, e-books and everywhere we turn.

Many of us saw the technical feasibility and value of “browser-based authoring” of Web content very early. For example, my team made remote authoring a key feature of the “Web Catalog” system we developed at NeXT and Apple way back in the mid to late 1990’s. In that system, a user could remotely create, merchandise and deploy a new Web Catalog entirely through a Web Browser—which was very cool for the time.

Many saw the technical possibilities for user-generated content almost as soon as the browser was invented. In fact, Tim Berners-Lee created the original web browser so that people could easily share their technical papers and discoveries with each other. Still most of us—and certainly I myself—ended up being very much surprised by the intensity with which the world embraced the opportunity for self-expression provided by social media. I’m still stunned that over 30 million people in the US alone author blogs—that’s one in every ten people! And even more than that number produce other forms of internet content, such as facebook posts and tweets.

From my perspective and from a somewhat technical standpoint, the key aspects of social media that give it tremendous power are ubiquitous access and the asynchronous nature of the communication.

- By ubiquitous, I mean that anyone with appropriate permissions can see social media posts. This offers a potential audience to the authors of content, large or small, which motivates them to produce it in the first place. For content consumers, ubiquitous access gives them the possibility that they will discover material that is relevant and meaningful to them, however specific their interest. Specific interests may include the activities of your friends and family. Or perhaps it may be some rather specialized field of interest, like lace-making or folk dancing, which may only be shared by a small to microscopic percentage of the population. Ubiquitous access (plus good search capabilities) offers at least a possibility that people with very specific interests can find each other and perhaps widen their circle of knowledge, friends and interests. Among other things, this has enabled marketplaces and businesses to flourish even if they cater to a very limited and distributed population—pipe smokers, handcrafters, or historical re-enactors, for example. The ability to bring like-minded people together to share information and form a market has implications for the products and services we buy in the physical world as well as the virtual one—mostly, to my mind, for the better.

- Asynchronous access means that content which is authored at one point in time may be read at a completely different point in time. Dialogs can last days, months or years between responses while still retaining context. The impact of this asynchronous access means that you and I don’t need to schedule a time and place to meet to communicate ideas—I can do it when it works for me, and you can do it when it works for you. This has the effect, among other things, of erasing time and distance. The fact that I am in California’s Silicon Valley in the year 2012 as I write these words does not mean my potential audience is local, or that it needs to be in same room or be on-line at the same time. Once I post this you can read it (or not) at your convenience in your timezone, and neither one of us needs to care about where we are and when we are posting or reading.

I see social media as one of the more profound phenomena affecting global society today. By connecting people who previously thought they were alone with a particular experience, social media is both re-invigorating specialized interests and allowing people to make common cause around social issues that trouble them. One recent example of social issues is “bullying”—that is, a set of children teasing or physically harming another child because he or she is different in some way. According to a recent report I heard on the news, bullied children and their parents previously felt very isolated, but with the advent of social media they have realized other children have the same experience. This realization has led these children and parents to get media attention focused on this problem, and to address it by school reforms and legislation.

There are many such examples of social movements arising from the connections made through social media. A profound one, of course, is the downfall of various regimes in the Middle East by individuals connected through social media such as Twitter.

- The Agile software development paradigm

- Smart devices, tablets and “physical world” aware devices (location-based services, etc.)

- Self-authoring and publishing of content on the world-wide web (facebook, twitter, blogging, “web 2.0”)

Agile

Another trend that began in the early 2000’s and has continued is “Agile” software development. Certainly the speed at which new software is being produced has grown many-fold over the last decade.

[1] While just about everyone now takes credit for the invention of the cloud—I’ve seen claims dating back to the 1960’s—I date it here to the launch of Amazon Web Services with EC2. AWS and EC2 clearly define what we mean today when we speak of “the cloud”.

[2] http://www.jeffbullas.com/2012/08/02/blogging-statistics-facts-and-figures-in-2012-infographic/

NOTE FROM 2025: I didn’t complete the section on Agile back in 2012, but distributed Agile development has proven itself to me to be the most effective way to do distributed development at scale. The “trick” is that individual teams of, typically, 6-8 people need to be either co-located or in compatible enough timezones to allow real-time collaboration. Depending on people’s sleep patterns and means of communication, that may or may not require geographical proximity. But real-time contact for the bulk of the working day is key to the success of a given team. Within that constraint, different teams can be located anywhere, with collaboration between teams co-ordinated through mechanisms like scrum-of-scrums, SAFe, and so on. I have found this to be effective across continents for teams up to many hundreds of people in size. I expect that even though GenAI will radically transform software development, the essence of the Agile process will still drive development in this next GenAI-driven development era; see my Whitepaper on the subject in the Media section.

This series, written for my then-30th Anniversary as a professional software developer in 2012, consists of the following parts: “pre-history” (before I began working professionally in 1982), 1982-1992, 1992-2002, this blog (2002-2012), and my predictions for the next 30 years, from 2012 through 2042.

Leave a reply to Philosophical musing on my 30th Anniversary in Software (August 2012) – Digitally Indigenous Content Cancel reply